Between Judea on the central mountain range and the coastal plain where you find Gaza (One city we didn't visit.) there are low foothills that were ideal for building cities. High enough to defend, low enough to dig a well and surrounded by fertile little valleys, 'cities' were popping up like mushrooms after the rain 3000 years ago. For as long as any of the locals could remember, this area had been Canaanite under Egyptian management. But now there were some new players sitting at the table and the Canaanites had folded and stakes were high.

The new high rollers were Israelites and Philistines, and how they happened to show up in Canaan at exactly the same time takes us back a few (hundred) years to Egypt.

Most people have at least heard of the account of the Israelites' exodus out of Egypt, which of course is told from the Hebrews' point of view. The Egyptian version is quite different. At the time rumor had it that a bunch of Hebrew slaves had cut work and slipped away into the desert. Ramses II, the pharaoh at the time, rounded up all the king's horses and all the king's men and charged off after the runaways.

Folks started asking questions when he came back alone.

"Where are the slaves, and now that you think about it, where are your soldiers?"

Ramses had some advisors that were a little bit better at their job than his generals. Their spin was this: Pharaoh had killed off all the Children of Israel and the last time he heard of his soldiers, they were deep sea diving in the Red Sea.

The Egyptian slave owners weren't happy, but what could you do?

A few years later everyone had forgotten about the Hebrews because the latest was that Sea Peoples were sacking one city after another on the Mediterranean seaboard. Ramses sent the Egyptian version of Paul Revere up the coast to their forward positions in Canaan with instructions to return with news of the invaders, one lantern if by land, two if by sea. A few days later he returned with three.

Ramses mustered his army and navy. (He had learned the hard way not to drive his chariots into the sea.) We don't know how the battles on land and on sea turned out, but in the end sea peoples and not Egyptians were settled in Canaan. Pharaoh's advisors knew how to handle the press and drew huge posters of naval victories and chariot battles on the palace walls with a caption about how Pharaoh had magnanimously settled his defeated foes in Canaan. (These posters exist to this day.)

Most historians won't agree with some of my version of events, but all agree that the archeological evidence points to the Sea Peoples and the Israelites entering the stage of history in Canaan at more or less the same time – around Ramses II reign in the 13th century B.C.E.

The Israelites were 12 tribes, and the Sea Peoples had tribes too. The Dananu, the Shardanu, and the Philistines, but everybody just called the whole bunch Philistines because all the Sea Peoples look alike anyway.

The Israelites took their sweet time making their way to the promised land and 40 years after leaving Egypt they entered Canaan from the east. Meanwhile, the Philistines had already set up shop on the coast, which is understandable, them being sea people and all. For a while the two nations didn't bother each other; the Israelites were up in the mountains building cities and walls and kicking Canaanite butt, and the Philistines were busy building ports on the Mediterranean and kicking Canaanite butt. But eventually the Canaanites had enough and moved to Egypt, and Israelites coming down from the mountains started to clash with Philistines moving inland.

And the big question was this: who was going to inherit the land?

The first city we came to was Ekron (Which is not to be confused with Acorn, Oregon, a hamlet even dinkier than Crabtree Corners.) Today the place is called Revadim and would have been considered a city in ancient times because it is surrounded by a security fence, but today they call it a kibbutz. .

The first city we came to was Ekron (Which is not to be confused with Acorn, Oregon, a hamlet even dinkier than Crabtree Corners.) Today the place is called Revadim and would have been considered a city in ancient times because it is surrounded by a security fence, but today they call it a kibbutz. ..

Ekron was a Philistine city and the Philistines had a lot going for them. They were really Greeks of course and had all the latest gadgets. In ancient times hi tech was iron technology. This was definitely an advantage when it came to fighting the hillbillies in Judea and didn't hurt the pocket either. Being Greeks, they always found a way to turn a profit, selling state of the art agricultural implements (iron plows) to Hebrew farmers and selling olive oil to the Egyptians.

Being open minded and progressive, the Philistines didn't have problems adopting the cultures around them. Kibbutz Revadim has recreated a typical Philistine city street for visitors where you can find an Israelite type four horned alter they used to worship their god Dagon and Egyptian style coffins in human form (I assume they didn't keep their coffins on main street, but it is an interesting touch.)

The Philistines were a very open minded bunch about culture, but a little less so when it came to neighbors. They were almost constantly at war with the Israelites. War back then amounted to a bunch of Philistines marching up to a hilltop and swearing at some Israelites gathered on a hill across the valley. The Philistines had a big guy named Goliath, so the Israelites were reluctant to run down to get their butts kicked, but they could run faster than Goliath so the Philistines had to settle for thinking up new cuss words (Which probably wasn't very hard, them being Greeks and all.)

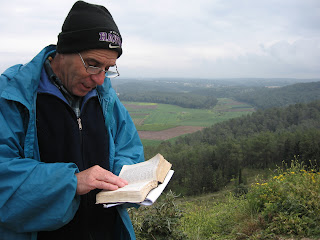

The site of the showdown between David and Goliath was in the Valley of Elah. It's one of those places where you can take a nature hike and let the Bible guide you. We climbed the hill where Israel camped and was verbally abused day after day by the overgrown brute from Gath. You can almost see the Israelites trembling in their armor and the shepherd boy gathering 5 smooth stones in the riverbed below.

The site of the showdown between David and Goliath was in the Valley of Elah. It's one of those places where you can take a nature hike and let the Bible guide you. We climbed the hill where Israel camped and was verbally abused day after day by the overgrown brute from Gath. You can almost see the Israelites trembling in their armor and the shepherd boy gathering 5 smooth stones in the riverbed below.The Philistines declined but didn't disappear after losing their champion. They held on to their cities on the sea and traded, with Israelites among others most likely. The Israelites built a mountain kingdom, and then fell out among themselves and split into two nations, Judea in the south and Israel in the north. In the end the issues between the Philistines and Israelites were settled by outsiders.

The next city we visited is Tel Lachish. Crabtree Corners isn't a city because it doesn't have a wall, but it does have a bar, a Church of Later Day Saints and a post office. Lachish didn't have Mormons, but they at least had a post office. We know this because letters written on broken pottery shards (They were fresh out of stationary.) from the garrison commander were found near the gate. He was writing a message to King Hezekiah. The Assyrians were at the gates.

The next city we visited is Tel Lachish. Crabtree Corners isn't a city because it doesn't have a wall, but it does have a bar, a Church of Later Day Saints and a post office. Lachish didn't have Mormons, but they at least had a post office. We know this because letters written on broken pottery shards (They were fresh out of stationary.) from the garrison commander were found near the gate. He was writing a message to King Hezekiah. The Assyrians were at the gates.The letters were never sent. The Assyrian king Sennacherib at the head of his army marched down the Via Maris and smote the Philistines, and then turned inland to subdue the defiant Judeans. The defenders of Lachish prepared their defense, but this time cussing out the enemy from a hilltop wasn't enough. The Assyrians filled up the ditch in front of the city walls and built an earth ramp up to the top, and stormed inside. Besides the unsent letters to Jerusalem for help, archeological finds like links from the chain the Israelites used to flip over Assyrian battering rams, thousands of arrowheads and hundreds of human skulls are evidence of the ferocity of the battle. Sennacherib recorded the victory on a bronze engraving in his palace depicting the battle. Along with the Biblical account, the Assyrians' testimony and the physical evidence in the field, Lachish one of the most documented battles in ancient history.

The story of the Philistines and Israelites is about a neighborhood dispute, and so if you're not one of the neighbors, it's almost humorous.

The story of the Philistines and Israelites is about a neighborhood dispute, and so if you're not one of the neighbors, it's almost humorous.Like when they have a battle and the Israelites take the Ark of the Covenant into battle with them. (Honestly, I've always wondered what on earth were they thinking, taking an ark with them to war.) The Philistines won of course, chased off the Israelites and took the Ark home with them as a trophy. That's when their troubles started. It turned out that the ark is a real pain in the butt. Literally. Every where they took it they would show off a bit and bam. Everybody had hemorrhoids. Finally they are dying to get rid of it, but afraid of offending the great hemorrhoid god of the Israelites. So they come up with this scheme to load it on a cart pulled by two heifers and send it on its way. The great hemorrhoid god would guide it home they reckoned.

And sure enough, the great hemorrhoid god who turned out to be the one and only true God guided it back to the Israelites who were sheepishly trying to figure out how to tell Him they lost it in the first place. One fine day the ark appeared out of nowhere at a city called Bet Shemesh, which was the last stop on our rainy day in the field.

And sure enough, the great hemorrhoid god who turned out to be the one and only true God guided it back to the Israelites who were sheepishly trying to figure out how to tell Him they lost it in the first place. One fine day the ark appeared out of nowhere at a city called Bet Shemesh, which was the last stop on our rainy day in the field.The sky had cleared and we saw the ruins of the ancient city across the road from the modern town of Bet Shemesh (Town, not a city; no wall, remember?). I didn't pay much attention to the explanation about the ruins because I was looking down the valley and thinking about how it must have been to see the Ark coming up on an ox cart. .

.

. On an afterthought, our instructor took us into town to 'Golan Sculptural Park'. It's named after Golan Pelai, the son of two sculptors who was killed in active duty. They work with stone and metal making art on biblical themes like Jacobs ladder and the Exodus.

And I thought about how little has changed in 3000 years. Israelites are now Israelis and two people are squabbling over the same little strip of land hugging the Mediterranean. Most of the time this conflict doesn't amount to much more than each side cussing out the other from modern hilltops; on T.V. and in the news. And sometimes fighting breaks out between modern day Goliaths and Davids. But the bottom line is that it's a dispute between neighbors, and while it's heartbreaking the way cities and civilians get trampled underneath, neither side will ever totally wipe out the other. If that happens it will most likely be the doing of some outsiders like Iran.

And I thought about how little has changed in 3000 years. Israelites are now Israelis and two people are squabbling over the same little strip of land hugging the Mediterranean. Most of the time this conflict doesn't amount to much more than each side cussing out the other from modern hilltops; on T.V. and in the news. And sometimes fighting breaks out between modern day Goliaths and Davids. But the bottom line is that it's a dispute between neighbors, and while it's heartbreaking the way cities and civilians get trampled underneath, neither side will ever totally wipe out the other. If that happens it will most likely be the doing of some outsiders like Iran.The Israelites were in the end carried away into captivity and exile, but the same stubborn nature that drew Assyrian and Babylonian fire kept them and their distinct culture alive over hundreds of years and thousands of miles away from their homeland. So when Jews returned to the land and became Israelis, their culture was the same Biblical one their forefathers had 3000 years ago.

As for the Philistines, they were carried off into the same captivity as the Israelites by Assyrians and Babylonians, but they evaporated into history. Nobody really knows what became of them. For all I know, their descendants might be living in Crabtree Corners.

All that’s left here of the Philistines is a name; Palestine. But that's another story.

1 comment:

found this very interesting,clear to read and beautifully described.

Sharon

Post a Comment